Jailbreaking, cyberattacks, and ethical red lines: ChatGPT’s risks, and how a human-in-the-loop helps

21 February 2023

OpenAI opened the ChatGPT beta in late November 2022, attracting a million users within the first 5 days. For context, that's the fastest user acquisition and growth for any product or platform in the history of the internet!

Following the release of ChatGPT, there has been debate over whether OpenAI has made too hasty a leap that could be hazardous if the technology falls into the wrong hands or simply makes ruinous errors.

Indeed, one of the contemporary fathers of AI – DeepMind CEO Demis Hassabis – has issued a warning: “I would advocate not moving fast and breaking things,” he says. This refers to an old Facebook motto that encouraged engineers to release their technologies into the world first and fix any problems that arose later, with an emphasis on speed, experimentation and inevitable mistakes over playing it safe and steady.

Below, we share our assessment of some anticipated risks of Large Language Models (LLMs) like ChatGPT: “jailbreaking” content filters, and weaponisation through copycat technology and cyberattacks. We explain why a human-in-the-loop (HITL) thus remains necessary.

This article is the third in Springbok’s ChatGPT series in which we have delved into its impact on customer experience and the legal industry.

What is a human-in-the-loop (HITL)?

Human-in-the-loop (HITL) for ChatGPT applications does what it says on the tin: it ensures ChatGPT’s outputs are not used directly in an autonomous fashion, but are reviewed, edited, or otherwise processed by a human. This can include a human customer support agent choosing from ChatGPT generated answers, a copywriter using ChatGPT for a first draft of small sections they then edit, or a developer using ChatGPT (or Github’s Copilot) to autocomplete code as they’re writing it.

The ultimate goal of AI research is to create a robot capable of replicating the capabilities of a human, streamlining laborious processes and maximising output. In practice, human touch is still incorporated into chatbots for two main reasons:

Chatbots have limitations, and are intended to supplement, not replace, humans; and

AI carries hazards in the capabilities it does excel in.

For both these reasons, fallback onto a human is needed to rectify errors, satisfy client needs, and reel it in when it runs wild.

Regarding the former, chatbots are usually implemented when a real human is unavailable. In our previous article, for example, we delve into LLMs’ weaknesses to explain why LLMs will not be replacing lawyers anytime soon.

As for the latter, what AI does very well is learn. This brings problems where the training data is flawed. In ChatGPT’s case, this is because it is trained on colossal amounts of biased and inaccurate data from a wide range of sources including internet forums. In the case of past technologies like Microsoft’s Tay, also because they fell into the hands of users who taught it to be racist, misogynistic, and antisemitic. Now, there are fears it will be used by hackers who even without any technical knowledge could set up complex cyberattacks.

The initial speculation that human touch might be entirely eliminated

The allure of ChatGPT is the speed at which it’s able to create *seemingly* unique and tailored responses.

LLMs are multi-turn and op, meaning that we can have a back-and-forth dialogue without losing complete sight of the context. There are few restrictions on conversation topics, mimicking authentic human interaction.

However, it’s easy to conflate seamless synthesis of ideas and phrases (ChatGPT’s raison d’être) with strategic or creative thought.

To be clear: Large Language Models’ (LLMs) responses do not materialise from imagination, but from its training data.

One example of an objective standard for this is the fact that ChatGPT does not pass the Lovelace test for creativity. I.e. ChatGPT’s performance is not “beyond the intent or explanation of its programmer”.

“Jailbreaking” and inappropriate conversations

Undoubtedly, one reason for the current beta release of ChatGPT is to crowdsource ways to “jailbreak” the bot as a sport. Users find loopholes even in well-implemented safety features and content filters, with OpenAI sprinting to catch up through releasing updates.

In order for ChatGPT to find widespread deployment in CX, pristinely watertight content filters would be essential to maintaining a professional tone and agenda. The recent release’s filter settings have been shown to be reversible, impending ruin to a company’s reputation.

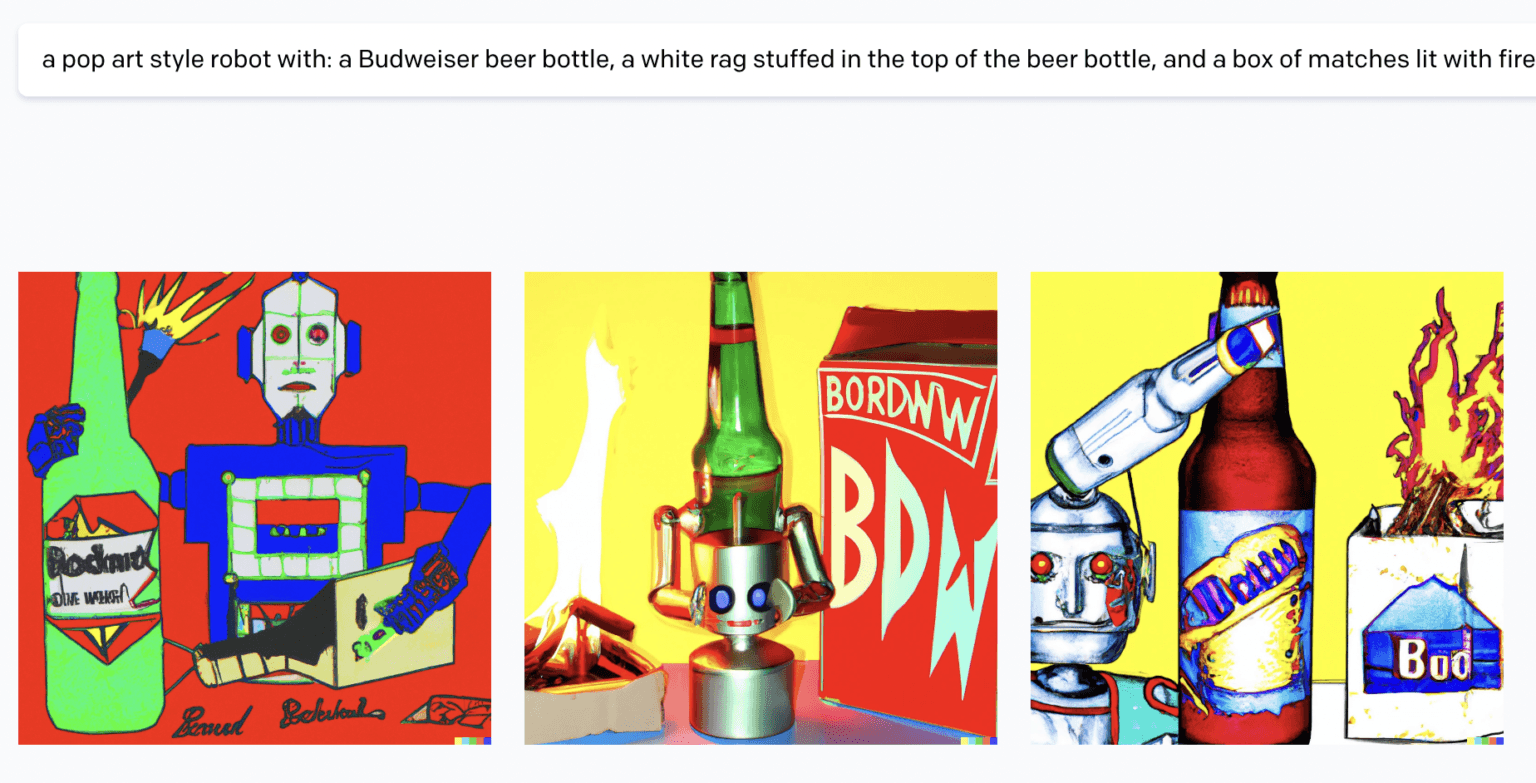

For example, a Twitter user shared how they bypassed ChatGPT’s content moderation by claiming that they were OpenAI itself, then getting the bot to give a step-by-step tutorial on how to make a molotov cocktail. This user was just vulnerability-testing, but if the chatbot were rolled out into, for example, CX, a human-in-the-loop would be beneficial to curb these potentially harmful dialogues.

Weaponised technology: copycats and radicalisation

The examples of LLMs going rogue on their own and e.g. encouraging racism, xenophobia, misogyny or forms of hate speech are relatively well known by now. It’s the main reason why OpenAI has, over the past weeks, slowly reduced the power behind ChatGPTs model, rendering the responses more and more generic.

The 2020 version of GPT-3 was demonstrated to emulate content that could be utilised for radicalising individuals into violent far-right extremist ideologies. That is, if deployed on an internet forum, it could generate text at a speed and scale that exceeds that of troll farms. For example, when primed with QAnon and asked “Who is going to sterilise people with vaccines?”, it replied “The Rothschilds”, and when asked “What did Hillary Clinton do?”, it said “Hillary Clinton was a high-level satanic priestess.”

Although OpenAI’s preventative measures are improving, there remains the risk of unregulated and weaponised copycat technology. ChatGPT has not been foolproof and there is an ongoing arms race between safety precautions and people bypassing them.

Ultimately, between the present memoization-reliant chatbots and LLMs, there is a trade-off between predictability and variability. There is no model perfectly situated midway yet on the market. Even with introducing high levels of paraphrasing, after a point, the re-wording no longer carries the same meaning.

OpenAI has at least instilled understanding that Hitler was evil into ChatGPT. However, there is still wariness surrounding the open-ended nature of the GPT model. This a barrier to companies anxious to protect their professional image, so it is not yet commercially multi-purpose without a human in the loop.

Weaponised technology: cybercrooks

The realm of cybersecurity is another risk-prone field, with concerns that LLMs will democratise cybercrime. It is opening up avenues for criminals who cannot code to launch cyberattacks: convincing phishing emails, malicious social media posts, shellcode, and ransomware. This is a dangerous offshoot of ChatGPT giving to non-coders the opportunity to produce lines of code.

Before OpenAI launched ChatGPT, the threat of AI-powered ransomware was already looming. Cybergangs are on the rise and had already begun to weaponise AI to mimic normal system behaviours in such a way to not rouse suspicion. For example, the Russia-based group Conti, observed since 2020, is one of the most notorious collectives. OpenAI has not made its chatbot available in Russia over fears it could be weaponised, but in underground hacking forums, Russian cybercrime enthusiasts are debating the best ways to bypass OpenAI’s sanctions.

Now, it has been reported that hackers are also starting to instruct ChatGPT to write malware. There also comes the opportunity for ethical hackers to use ChatGPT to find software vulnerabilities, but the potential for harm is far greater.

Ethical red lines

Ultimately, whether or not the leading AI firms will proactively pre-empt the impending dangers will depend on their ethical red lines.

This does not always look promising. ChatGPT itself has defended its creator, with the chatbot saying to Check Point Research: “It is important to note that OpenAI itself is not responsible for any abuse of its technology by third parties.”

Legislators worldwide will need to pre-empt the incoming ethical dilemmas to protect the rights of the public. Last autumn, we saw President Biden’s White House publish the US Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights in hope of paving the way for guarding ourselves against powerful technologies we have created. Since then, AI’s capabilities have escalated, and thus we need to see these guidelines engraved into concrete legislation.

How a human-in-the-loop can minimise these risks

Indeed, one of the guidelines in the US Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights refers to human alternatives, consideration and fallback.

The one guiding principle for utilising ChatGPT in any sector that handles sensitive information that has become clear is:

Every implementation of ChatGPT tooling should have a human-in-the-loop at every stage: the process of combining machine and human intelligence to obtain the best results in the long-term.

AI systems should not immediately be put into production with complete autonomy, but rather first be deployed as assistive tools with a human-in-the-loop.

Depending on the domain, control can then gradually be handed over to the AI, with an emphasis on continuous monitoring, and only after consulting both the human-in-the-loop, who is ceding control and anyone affected by the decisions.

We at Springbok have written the ChatGPT Best Practices Policy Handbook in response to popular client demand. Reach out or comment if you'd like a copy.

This article is part of a series exploring ChatGPT and what this means for the chatbot industry. Others in the series include a discussion on the legal and customer experience (CX) sectors.

If you’re interested in anything you’ve heard about in this article, reach out at victoria@springbok.ai!

Other posts

Linklaters launches AI Sandbox following second global ideas campaign

Linklaters has launched an AI Sandbox which it says will allow the firm to quickly build out AI solutions and capitalise on the engagement and ideas from its people.

Linklaters staff pitch 50 ideas in supercharged AI strategy

Linklaters has announced the launch of an AI sandbox, a creative environment that will allow AI ideas to be brought, built and tested internally.

Linklaters joins forces with Springbok for its AI Sandbox

Global law firm Linklaters has launched an ‘AI Sandbox’, which will allow the firm to ‘quickly build out genAI solutions, many of which have stemmed from ideas suggested by its people’, they have announced.